Promoting Sustainable Innovations in Plant Varieties

Promoting Sustainable Innovations in Plant Varieties

My Ph.D. thesis, titled “Promoting Sustainable Innovations in Plant Varieties: Revisiting “Creative Destruction” and “Market Failure” was published a couple of years ago by Springer Nature under the simplified title: “Promoting Sustainable Innovations in Plant Varieties.” The Ph.D. was fully funded by a fellowship from the International Max Planck Research School for Competition and Innovation (IMPRS-CI) during 2009-2013 and recieved top grades (Summa cum Laude) from both academic reviewers. The book has recived considerable attention since its publication. A very creative, engaging and unusual review of the book was recently written by Prof. Graham Dutfield (University of Leeds), and was published by Elsevier (see here). Here I provide an overview of some of the findings of the book, which, in my view, might be the most exciting for anyone researching this field. This overview has also been published in the latest Progress Report (Tätigkeitsbericht) of the Max Planck Institute for Innovation and Competition.

Promoting Sustainable Innovations in Plant Varieties,Mrinalini Kochupillai. Springer, Berlin, Heidelberg (2016). xxi + 335 pp., ISBN: 978-3-662-52795-5

The study develops the term “sustainable innovations” and defines it, in the context of plant variety innovations, as innovations that by their very nature (i) permit in situconservation, improvement and evolution of agrobiodiversity; (ii) maintain the rich genetic variability inherent in this agrobiodiversity in diverse geographic and climatic conditions; (iii) do not exclude any potential innovators from the process of innovation; and (iv) thereby ensure that both formal and informal innovations can continue to take place in the generations to come (in both the developed and developing world). Accordingly, the Indian Plant Variety Protection Act, the UPOV Acts and associated agricultural policies are studied from a legal, philosophical, historical and economic perspective with the aim of determining the means of promoting sustainable innovations in plant varieties and identifying laws, policies and practices that are currently acting as impediments to promoting and accomplishing the same.

The study looked into the following research questions from a multi-disciplinary and/or empirical perspective: How should the study define the term “sustainable innovations”? What means (at the legal, policy and practical levels) are currently adopted (internationally) to promote any kind of innovation in plant varieties? Do these means also promote “sustainable innovations”? Are there any facts, circumstances, policies, laws or practices that make the accomplishment of the ideal of promoting sustainable innovations, difficult or impossible? What are the trends vis-à-vis seed saving, seed improvement/innovation and in situ agrobiodiversity conservation among farmers of various regions in India, for various crops?

A partially mixed, concurrent and sequential, equal status design was adopted for the study (i.e., mixed methods research, combining qualitative and quantitative research methods). For the qualitative research, the historical research method, combined with traditional legal literature review, interviews with relevant stakeholders and descriptive analysis of qualitative data so collected, was undertaken. For the quantitative research, data was collected using the stratified random sampling scheme, with the help of a structured questionnaire. Econometric analysis using Stata was conducted on the quantitative data collected via farmer interviews. As is a suggested practice in partially mixed research, the “mixing” of the qualitative and quantitative findings was done at the data interpretation stage.

Using this methodology, the book investigates and questions some commonly made presumptions on which the current plant variety protection regime in India and under UPOV (1978 or 1991) are based: It is frequently presumed that seed saving by farmers to save costs associated with purchase of new or improved seeds from the market is an equally prominent trend among farmers in various regions of India, notwithstanding the land holding size, the level of education, and/or the crop being cultivated by the farmers. In fact, the farmers’ exemption under the Indian law as well as under UPOV (1978) are based largely on this presumption. Empirical research conducted as part of this study, in two regions of India, involving more than 200 farmers, agricultural extension officers and academic researchers proved otherwise. Further, in the Indian context, it was expected that following the adoption of the Indian PPV & FR Act, the private and public sector’s interest in R&D will become more diversified to include self-pollinating crops and typical seeds, and will not continue to focus on crops whose floral biology is conducive to creating F1 hybrids that prevent farmer level seed saving. A detailed statistical analysis of the plant variety protection applications filed in India from 2007-2013 again revealed the opposite.

The book finds that from a normative perspective, neither the Indian Protection of Plant Varieties and Farmers’ Rights Act, 2001 (PPV & FR Act), nor the UPOV texts are equipped to address the market failures that are unique to the plant variety innovations sector in developed or developing countries; neither are they fully suited to promoting sustainable innovations in plant varieties. In fact, the Indian Plant Variety Protection Act and similar regimes that promote optimal innovations in plant varieties tend to undermine and even actively disincentivize farmer level seed innovation and in situ agrobiodiversity conservation. Indeed, since in situ agrobiodiversity conservation through saving and exchange of traditional as well as newer seed varieties, is a perquisite and even a synonym of farmer level seed innovations, intellectual property rights and associated policies such as the seed replacement policy of the Indian government, act as ‘perverse incentives’, turning farmers away from their traditional role of conserving and improving seeds in situ.

Further, technological development in the formal seed sector (private sector), which permits the creation of F1 hybrid seeds (as well as newer technologies engaging cytoplasmic genetic male sterility or GURT technologies) that do not reproduce true to type and preclude farmer seed saving, are, in themselves, adequate to incentivize private sector participation in plant varieties innovation. A study of plant variety protection data from India clearly shows that even after the adoption of the PPV & FR Act, the private sector in India is engaged in R&D primarily for crops whose floral biology permits the creation of F1 hybrids (e.g. tetraplod cotton, maize, pearl millet). Private sector R&D is almost entirely absent in self-pollinating crops, especially pulses. Accordingly, the passage of the PPV & FR Act has not accomplished its aim of promoting private sector R&D, and those crops that were neglected by private sector (R&D) before the introduction of the Act, continue to be neglected even now.

The PPV & FR Act as well as provisions in UPOV 1978 and similar legislations that support farmer level seed saving (inter alia, for sowing subsequent generations of crops) presume that farmers, if given a choice between saving seeds from a harvest for sowing the next generation, versus buying new (improved) seeds from the market in each subsequent sowing season, would choose to save seeds. Empirical (quantitative) data collected via farmer surveys suggests that this is not true; farmers, when faced with such a choice, choose improved seeds and abandon traditional in situ agrobiodiversity conservation and seed improvement efforts. This choice is guided and encouraged by the seed replacement policy of the government of India. Conservation trends are seen only in crops for which “improved” varieties are not available in the market. This finding calls to question the rationale of provisions codifying the farmers’ privilege, especially when parallel and stronger efforts are underway to encourage farmers’ purchase of formally improved varieties.

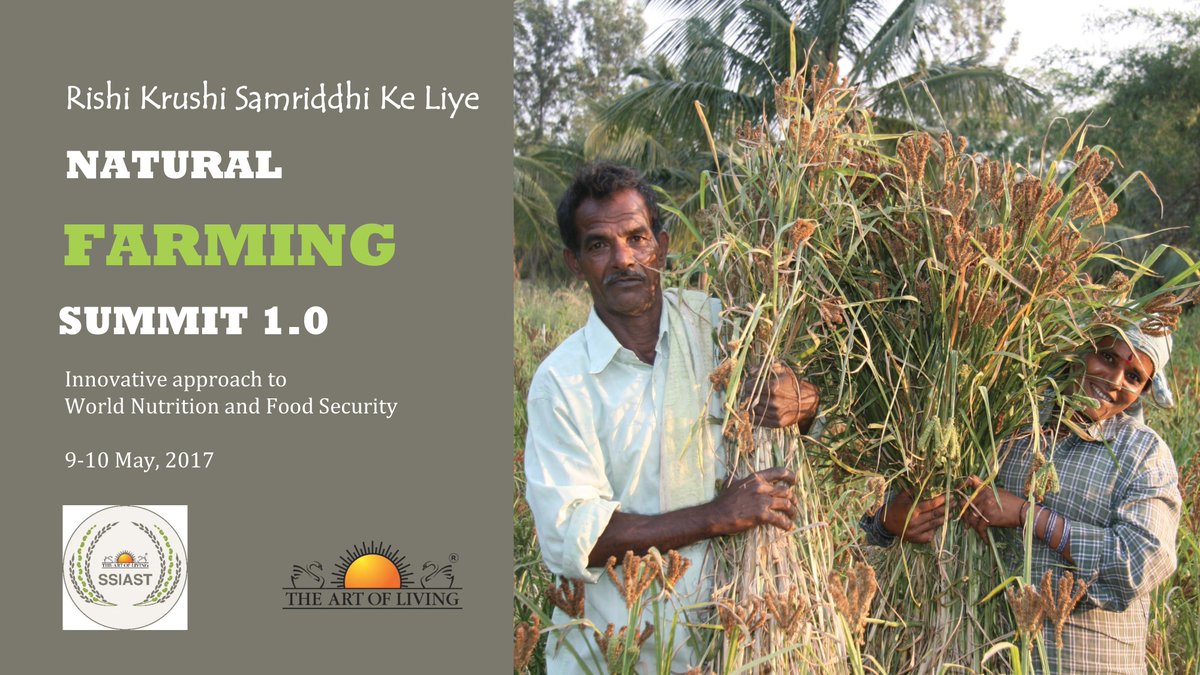

National and international (government) policies and laws that are currently supporting private/public (formal) sector R&D and innovation in plant varieties over and above innovation in the informal (farmers’) sector have the effect of excluding farmers from the innovation eco-system. Farmers, that have traditionally been innovators, are rapidly reduced to the status of labourers. Modern, input intensive agriculture that requires farmers to not only buy new seeds, but also pesticides, fertilizers and water to ensure the high performance of these seeds has also left farmers caught in a debt trap, leading, in some regions, to large scale farmer suicides. The innovation environment and eco-system needs therefore to be redesigned with a focus on promoting sustainable innovations, including especially in the informal (farmer) seed sector.

The findings of the book have been taken forward in a project titled “Intellectual Property and Global Develoment” funded by the UK Arts and Humanities Research Council. The details of the project are available here.

Recent Comments